A Greek Othello

Othello

09 Jul 2021

/ 09:46

Article by Costas Vergos

Here are the words of Iago in Shakespeare's ‘Othello’: “In following him, I follow but myself; not for love or duty, but only for my secret purposes. I am not what I am.” In Verdi's opera of the same name, Iago is even more cynical and Machiavellian: Credo in un Dio crudel! (“I believe in a cruel God!” - libretto by Arrigo Boito).

In ‘Othello’, all the heroes are miserable and merciless. Everyone except Dysdaimona. But she too: what is this name given to her by Giraldi Cinthio, the author of the novel that inspired Shakespeare? Dys-demon. Her sin, according to Cinthio, was that, being a Venetian noblewoman, she married a Moor, a very provocative act at that time in ‘white’ Venice. And that's where it all started.

Othello, a formidable warrior in the service of Serenissima, had a permanent ‘flaw’: he was black, Moor. But he also had an even deeper, real now, flaw: as ‘different’ he was possessed by a complex of insecurity, gullibility and blind jealousy towards his wife (self-feeding feeling).

Almost four times more verses than Othello’s are dedicated to Iago. Verdi wanted to call his opera ‘Iago’. (Boito disagreed.) Everyone here (in the play and in the opera) is bad, but, without Iago, this without cause exemplary cunning and slander man of the world letters, nothing would have happened. Yes, the fact that he was passed over by Cassio as Othello's deputy leader and the fact that he had some suspicions about his own wife's infidelity are not grounds for such a high-intelligence plan to destroy so many people. Iago had planned everything, turning them against each other, so that in the catastrophe he would not appear guilty (until, at the end of the play, his satanic plan was revealed).

In his first aphoristic book, ‘Human, Very Human’, Nietzsche says: “History seems to give the following instructions about the rise of genius: to mistreat and torture people, exploiting the passions of envy, jealousy, hatred and rivalry. To lead people to the extreme ends against each other… Whoever knows how genius was created, would like to follow the usual process of nature, that is, they should be just as malicious and ruthless as nature.” (And then, we must note, there is a quote by the German philosopher as to whether this is not really the case.)

Tragedy is action, drama and discourse about the ultimate and highest evil. But, while in the ancient Athenian tragedy, the heroes are initially good to finally end up hurting each other, in the Elizabethan tragedy the heroes are bad from the beginning to the end. These (despite the addition of chorus to the performance we saw these days) are two different genres with, in terms of conception, superiority of the first one.

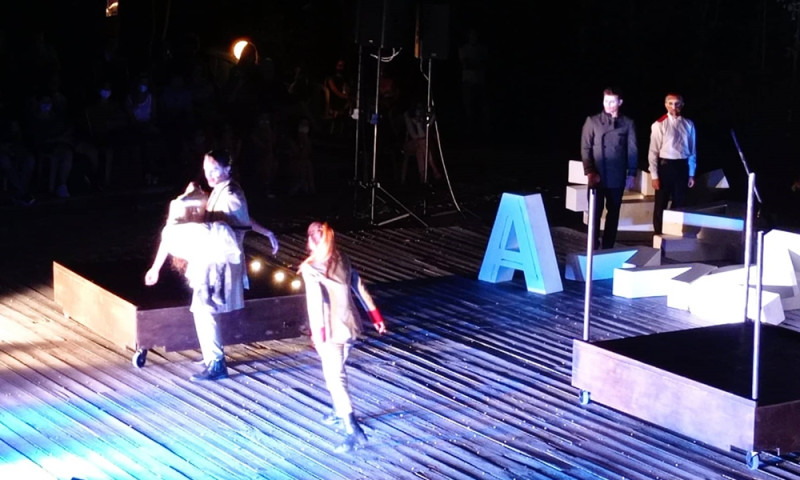

The Greek Othello, Giannis Bezos, played as Shakespeare would have liked. How else would he express gullibility and other character weaknesses if the actor did not come from comedy with its distinctly familiar grimaces? The Greek Iago, Emilios Cheilakis, was an excellent Iago. It was a wonderful theatrical performance that people of Corfu enjoyed these days.

In ‘Othello’, all the heroes are miserable and merciless. Everyone except Dysdaimona. But she too: what is this name given to her by Giraldi Cinthio, the author of the novel that inspired Shakespeare? Dys-demon. Her sin, according to Cinthio, was that, being a Venetian noblewoman, she married a Moor, a very provocative act at that time in ‘white’ Venice. And that's where it all started.

Othello, a formidable warrior in the service of Serenissima, had a permanent ‘flaw’: he was black, Moor. But he also had an even deeper, real now, flaw: as ‘different’ he was possessed by a complex of insecurity, gullibility and blind jealousy towards his wife (self-feeding feeling).

Almost four times more verses than Othello’s are dedicated to Iago. Verdi wanted to call his opera ‘Iago’. (Boito disagreed.) Everyone here (in the play and in the opera) is bad, but, without Iago, this without cause exemplary cunning and slander man of the world letters, nothing would have happened. Yes, the fact that he was passed over by Cassio as Othello's deputy leader and the fact that he had some suspicions about his own wife's infidelity are not grounds for such a high-intelligence plan to destroy so many people. Iago had planned everything, turning them against each other, so that in the catastrophe he would not appear guilty (until, at the end of the play, his satanic plan was revealed).

In his first aphoristic book, ‘Human, Very Human’, Nietzsche says: “History seems to give the following instructions about the rise of genius: to mistreat and torture people, exploiting the passions of envy, jealousy, hatred and rivalry. To lead people to the extreme ends against each other… Whoever knows how genius was created, would like to follow the usual process of nature, that is, they should be just as malicious and ruthless as nature.” (And then, we must note, there is a quote by the German philosopher as to whether this is not really the case.)

Tragedy is action, drama and discourse about the ultimate and highest evil. But, while in the ancient Athenian tragedy, the heroes are initially good to finally end up hurting each other, in the Elizabethan tragedy the heroes are bad from the beginning to the end. These (despite the addition of chorus to the performance we saw these days) are two different genres with, in terms of conception, superiority of the first one.

The Greek Othello, Giannis Bezos, played as Shakespeare would have liked. How else would he express gullibility and other character weaknesses if the actor did not come from comedy with its distinctly familiar grimaces? The Greek Iago, Emilios Cheilakis, was an excellent Iago. It was a wonderful theatrical performance that people of Corfu enjoyed these days.